Ajanta Caves (Devanagari:अजंठा लेणी) in Maharashtra, India are rock-cut cave monuments dating from the second century BCE, containing paintings and sculpture considered to be masterpieces of both “Buddhist religious art” and “universal pictorial art”. The caves are located just outside the village of Ajinha in Aurangabad District in the Indian state of Maharashtra (N. lat. 20 deg. 30′ by E. long. 75 deg. 40′). Since 1983, the Ajanta Caves have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site. A National Geographic edition reads, “The flow between faiths was such that for hundreds of years, almost all Buddhist temples, including the ones at Ajanta, were built under the rule and patronage of Hindu kings.”

Get In

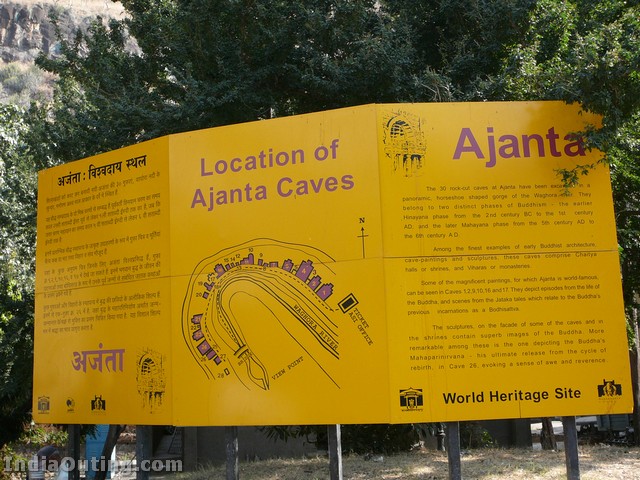

The caves are in a wooded and rugged horseshoe-shaped ravine about 3½ km from the village of Ajantha. It is situated in the Aurangābād district of Maharashtra State in India (106 kilometers away from the city of Aurangabad). The nearest towns are Jalgaon (60 kilometers away) and Bhusawal (70 kilometers away). Along the bottom of the ravine runs the river Waghur, a mountain stream. There are 29 caves (as officially numbered by the Archaeological Survey of India), excavated in the south side of the precipitous scarp made by the cutting of the ravine. They vary from 35 to 110 ft (34 m) in elevation above the bed of the stream.

History

The monastic complex of Ajanta consists of several viharas (monastic halls of residence) and chaitya-grihas (stupa monument halls) cut into the mountain scarp in two phases. The first phase is mistakenly called the Hinayana phase (referring to the Lesser Vehicle tradition of Buddhism, when the Buddha was revered symbolically). Actually, Hinayana – a derogative term for Sthaviravada – does not object to Buddha statues. At Ajanta, cave numbers 9, 10, 12, 13, and 15A (the last one was re-discovered in 1956, and is still not officially numbered) were excavated during this phase. These excavations have enshrined the Buddha in the form of the stupa, or mound.

By AD 480 the caves at Ajanta were abandoned. During the next 1300 years the jungle grew back and the caves were hidden, unvisited and undisturbed until the Spring of 1819 when a British officer in the Madras army entered the steep gorge on the trail of a tiger. Somehow, deep within the tangled undergrowth, he came across the almost hidden entrance to one of the caves. Exploring that first cave, long since a home to nothing more than birds and bats and a lair for other, larger, animals, Captain Smith wrote his name in pencil on one of the walls. Still faintly visible, it records his name and the date, April 1819.

Paintings

Paintings are all over the cave except for the floor. At various places the art work has become eroded due to decay and human interference. Therefore, many areas of the painted walls, ceilings, and pillars are fragmentary. The painted narratives of the Jataka tales are depicted only on the walls, which demanded the special attention of the devotee. The process of painting involved several stages. The first step was to chisel the rock surface, to make it rough enough to hold the plaster. The plaster was made of clay, hay, dung and lime. Differences are found in the ingredients and their proportions from cave to cave. While the plaster was still wet, the drawings were done and the colors applied. The wet plaster had the capacity to soak the color so that the color became a part of the surface and would not peel off or decay easily.

The colors were referred to as ‘earth colors’ or ‘vegetable colors.’ Various kinds of stones, minerals, and plants were used in combinations to prepare different colors. Sculptures were often covered with stucco to give them a fine finish and lustrous polish. The stucco had the ingredients of lime and powdered seashell or conch. The latter afforded exceptional shine and smoothness. In cave upper six, some of it is extant. The smoothness resembles the surface of glass. The paint brushes used to create the artwork were made from animal hair and twigs.