Stepwells, also called kalyani or pushkarani (Kannada: ), bawdi (Hindi: बावड़ी) or baoli (Hindi: बावली), barav (Marathi: बारव), vaav(Gujarati: વાવ) are wells or ponds in which the water may be reached by descending a set of steps. They may be covered and protected and are often of architectural significance. They also may be multi-storied having a bullock which turns the water wheel ("rehat") to raise the water in the well to the first or second floor.

They are most common in western India. They may be also found in the other more arid regions of South Asia, extending into Pakistan. The construction may be utilitarian, but sometimes includes significant architectural embellishments.

A number of distinct names, sometimes local, exist for stepwells. In Hindi-speaking regions, they include names based on baudi (including bawdi, bawri, baoli, bavadi, bavdi). In Gujarati and Marwari language, they are usually called vav or vaav.

All forms of the stepwell are examples of the many types of storage and irrigation tanks that were developed in India, mainly to cope with seasonal fluctuations in water availability. A basic difference between stepwells on the one hand, and tanks and wells on the other, was to make it easier for people to reach the ground water, and to maintain and manage the well.

In some related types of structure (johara wells), ramps were built to allow cattle to reach the water.[citation needed]

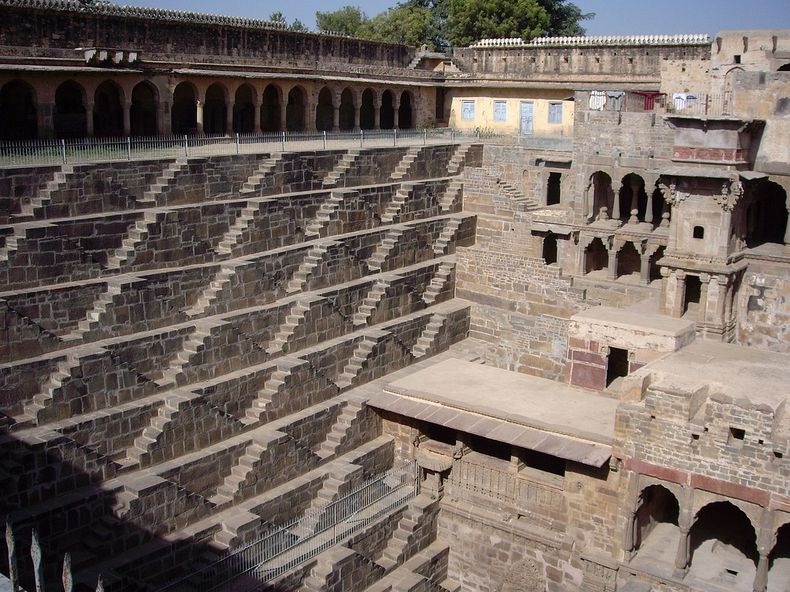

The builders dug deep trenches into the earth for dependable, year-round groundwater. They lined the walls of these trenches with blocks of stone, without mortar, and created stairs leading down to the water.[1] The majority of surviving stepwells originally also served a leisure purpose, as well as providing water. This was because the base of the well provided relief from daytime heat, and more of such relief could be obtained if the well was covered. Stepwells also served as a place for social gatherings and religious ceremonies. Usually, women were more associated with these wells because they were the ones who collected the water. Also, it was they who prayed and offered gifts to the goddess of the well for her blessings.[1] This led to the building of some significant ornamental and architectural features, often associated with dwellings and in urban areas. It also ensured their survival as monuments.

Stepwells usually consist of two parts: a vertical shaft from which water is drawn and the surrounding inclined subterranean passageways, chambers and steps which provide access to the well. The galleries and chambers surrounding these wells were often carved profusely with elaborate detail and became cool, quiet retreats during the hot summers.[2]

Water in the architecture of India could be found since the earliest times and had played an important role in the culture. Stepwells were first used as an art form by the Hindus and then popularized under Muslim rule.[2]

Stepwell construction is known to have gone on from at least 600 AD in the south western region of Gujarat, India. The practical idea even spread north to the state of Rajasthan, along the western border of India where several thousands of these wells were built. The construction of these stepwells hit its peak from the 11th to 16th century.[2] Most existing stepwells date from the last 800 years. There are suggestions that they may have originated much earlier, and precursors to them can be seen in the Indus Valley civilisation.

The first rock-cut step wells in India date from 200-400 AD.[3] Subsequently, the construction of wells at Dhank (550-625 AD) and of stepped ponds at Bhinmal (850-950 AD) takes place.[3] The city of Mohenjo-daro has wells which may be the predecessors of the step well; as many as 700 wells have been discovered in just one section of the city leading scholars to believe that 'cylindrical brick lined wells' were invented by the people of the Indus Valley Civilisation.[4]

One of the earliest existing example of stepwells was built in the 11th century in Gujarat, the Mata Bhavani's vav. A long flight of steps leads to the water below a sequence of multi-story open pavilions positioned along the east/west axis. The elaborate ornamentation of the columns, brackets and beams are a prime example of how stepwells were used as a form of art.[5]

The authorities during the British Raj found the hygiene of the stepwells less than desirable and had installed pipe and pump systems to replace their purpose. The stepwells had social and religious activities significance. The Mughal rulers did not disrupt in the culture that was practiced in these stepwells and encouraged the building of stepwells. It was to the British that forced abandonment of the wells, a continued loss of authority by the native rulers to the authority of the British and a part of the native culture.[5]

The importance of water to the locations in which they were found have been realized in the past decade now that many communities in the area have scarcity of rain and water. The construction of these wells encouraged the incorporation of water into the culture where they were popular. These stepwells were even proven to be well built after withstanding earthquakes in the range of 7.6 on the Richter scale.[1]

Numbers of surviving stepwells can be found in North Karnataka (Karnataka), Gujarat, Rajasthan, Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra. Significant ones include:

- Agrasen ki Baoli, New Delhi

- Rajon ki baoli, New Delhi

- Chand Baori in Abhaneri near Jaipur, Rajasthan

- Charthana Barav, Parbhani District, Maharashtra

- The Rani ki vav at Patan, Gujarat

- The Adalaj ni Vav at Adalaj, Gandhinagar, Gujarat

- Raniji ki Baori in Bundi, Rajasthan; Bundi has over 60 baolis in and around the town.

In Karnataka[edit]

- Stepped Well or Pushkarani near Mahanavami dibba Hampi or Vijayanagara, North Karnataka

- Stepped Well at Manikesvara Temple Lakkundi, North Karnataka

- Nagakunda Sudi, North Karnataka

- Venkatappa Naik royal bath Kanakagiri, North Karnataka

- Stepwell at Mallikarjun